The Rapture of Apostle Paul

With the kind permission of Fr Dr Maximos Constas, below is an excerpt from his chapter “The Reception of Paul and Pauline Theology in the Byzantine Period” in D. Krueger & R. S. Nelson (eds), The New Testament in Byzantium (Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection), 147–76.

The Paul of modern biblical studies, and to a significant extent of the modern Christian imagination, is a figure that has been largely constructed in the wake of the Reformation. Justification by faith, the mutual exclusivity of law and gospel, a radical doctrine of original sin and predestination, the repudiation of natural theology, and an opposition between faith and liturgical worship are among the predominant features of Paul as he appears in Wittenberg and Geneva. But there is another Paul, who, though relegated to the margins of modern biblical scholarship, stands at the very centre of the Byzantine exegetical and theological tradition. The Byzantine portrait of Paul places in bold relief the apostle’s dramatic conversion experience, his vision of the divine light, his self-identification with Christ, his ascent to the third heaven, and his gift of divine grace and wisdom—features that are generally grouped under the now politically incorrect category of Pauline “mysticism” and that remain by far the most neglected and misunderstood aspects of Paul’s life and work. These same features, however, figure prominently in the exegesis of the Greek fathers and especially the later Byzantine writers, in a unified tradition of Pauline interpretation extending from late antiquity to the end of the Palaiologan period and beyond. The Byzantine interpretation of Paul is an important area of study, both to better understand the later Byzantine theological tradition and for the retrieval of a uniquely meaningful option in the study of a figure whose importance for Christianity is second only to that of Christ himself.

Paul’s Rapture

The question of Paul’s visionary experiences and in particular his ascent or “rapture” (ἁρπαγή) into the third heaven is one which many modern scholars find disconcerting, if not a little alarming, inasmuch as the familiar Paul here changes into a believer in celestial wanderings. Accounts of “visions and revelations” (2 Cor. 12:1) and of journeys to “heaven” and “paradise” (2 Cor. 12:2, 4) make Paul seem more like a medieval Byzantine saint than a modern Protestant pastor, and argue for an image of the apostle as a man of “mystical” experiences in a way that scholars have found difficult to conceptualize. Yet none of this should be surprising, since Paul’s letters, as well as his depiction in the book of Acts, provide ample evidence of visionary experiences, revelations, and ecstasies; of miracles; of the indwelling of Christ and/or the Holy Spirit; of experiences of grace and spiritual transformation; and of personal union with Christ.

Paul’s account is the only firsthand description of an ascent to heaven to have survived from

the first century. It is tantalizingly brief—around fifty words—little more than an elliptical digression about “visions and revelations” embedded in a larger argument and therefore “difficult to understand” (2 Pet. 3:16). In the tradition of ironic boasting, Paul wrote of “a certain man” who was “caught up” into the “third heaven,” although he afterward stated that this man was “caught up” into “paradise,” where he heard “certain ineffable words that cannot be spoken.” To complicate matters still further, the apostle repeatedly noted that he did not know whether this experience took place “in the body or out of the body.” We are consequently left to wonder about the precise relation of the “third heaven” to “paradise,” which may perhaps be one and the same destination, unless Paul was speaking of a two-stage ascent, or perhaps of two separate ascents. Further ambiguity arises over whether or not this was a spiritual or a bodily experience; and we are told nothing about the content, meaning, or purpose of the revelation, or why the words that were heard cannot be communicated to others.

Despite these ambiguities—or perhaps because of them—this passage attracted considerable interest throughout the patristic and later Byzantine periods. On the whole, the church fathers accepted the account as entirely fitting and natural, recognizing in Paul's rapture a paradigm for their own spiritual experiences, a connection authorized by the influential Life of Antony. The connection itself, however, is much older, and appears in highly developed form already in Origen’s commentary on the Song of Songs, which conflated the connubial “inner chamber” with the apostle’s “third heaven.” The commentary survives only in a Latin translation (Commentarius in Canticum Canticorum), although the passage linking Paul’s ecstasy with Christian mystical experience is extant in Greek in the catena on the Song of Songs compiled by Prokopios of Gaza (ca. 460–526).

From at least the third century, spiritual writers interpreted Paul’s ascent as an expression

of the highest level of mystical experience. Undoubtedly, the most elaborate example of

such an interpretation is found in Maximos the Confessor, Ambigua 20. Maximos interpreted the event in the framework of his theology of divinization. He pointed out that divinization is not a natural potential of human nature, but the activity of divine grace, the reception of which requires a person to “go outside of himself,” that is, to enter a state of ecstasy, after the manner of Paul. Maximos subsequently embarked on a highly Dionysian interpretation of the apostle’s ascent to the third heaven, which, he argued, unfolded according to the three stages of purification, illumination, and mystical union.

The first stage encompasses (1) the “practical philosophy” of asceticism, (2) a renunciation of nature through virtue, or (3) a state of dispassion. The second stage is marked by (1) the transcendence of cognitions generated by the activity of sense perception, (2) the transcendence of time and space (i.e., the conditions in which objects of perception have their existence), or (3) “natural contemplation,” which is the comprehension of the intelligible foundations of phenomenal reality. The third and final stage is either (1) “dwelling” in God, (2) a restoration by grace to one’s divine source, or (3) initiation into “theological wisdom.” Because the latter triad is an ecstatic state marked by the cessation of both sensation and intellection, it is “not something that the apostle accomplished, but something that befell him,” and the only “activity” in actual operation belonged wholly to God. As for the meaning of the “third heaven,” Maximos offered two interpretations, either (1) the “boundary” or “limit” of each of the three stages that Paul attained or (2) the “three orders of angels immediately above us.” Through these orders Paul ascended by a process of negation and affirmation. By negating the knowledge of one order, the apostle was initiated into the rank immediately above it, “for the positive affirmation of the knowledge of what is ranked above is a negation of the knowledge of what is below, just as the negation of the knowledge of what is below implies the affirmation of what is above.” This process comes to a halt with the final negation of the “knowledge of God,” beyond which there can be no further affirmations, “since there is no longer any boundary or limit that could define or frame the negation.”

According to Maximos, it was the natural result of the apostle’s temporary loss of corporeal sensation and intellection that he did not know whether he was “in the body” or “outside the body.” Insofar as Paul had gone outside himself in ecstasy, his power of sense perception was inactive, and thus he was not “in the body.” But neither was he “outside the body,” insofar as “his intellective power was inactive during the time of his rapture.” Maximos averred that this is also why the words Paul heard cannot be repeated, for having, as it were, sounded in a realm beyond mind, they cannot be grasped by ordinary thought, or uttered through ordinary speech, or received by ordinary human hearing. Maximos concluded this complex interpretation by construing Paul’s threefold ascent as an expression of the spiritual progress that results from a life lived according to the Pauline virtues of “faith, hope, and love” (1 Cor. 13:13).

In Maximos’s reading of 2 Corinthians 12:1-4, Paul’s rapture is fully identified with ascetic contemplation and the experience of divinization. The “three heavens” signify—indeed simply are—the three stages of the spiritual life and their respective modes of cognition. The movement of “ascent” is thus a progression from lower to higher modes of cognition as the soul is increasingly abstracted from its bodily senses, passing into a realm beyond intellect. The condition of being “caught up,” of being “outside oneself,” is a signature Dionysian doctrine grounded on the ecstatic transport of Paul to the third heaven. Consistent with this tradition, Maximos allowed for an immediate experience of God in ecstasy, so that Paul’s rapture, far from being a unique or extraordinary event, coincided with the end for which Christian life is a preparation, namely, divinization. Among later Byzantine writers, this is the standard interpretation of 2 Corinthians 12:2-4, so that every saint becomes “another Paul (ἕτερος Παῦλος), caught up to the third heaven of theology” (Niketas Stethatos, Gnostic Chapters 44).

The Paul of modern biblical studies, and to a significant extent of the modern Christian imagination, is a figure that has been largely constructed in the wake of the Reformation. Justification by faith, the mutual exclusivity of law and gospel, a radical doctrine of original sin and predestination, the repudiation of natural theology, and an opposition between faith and liturgical worship are among the predominant features of Paul as he appears in Wittenberg and Geneva. But there is another Paul, who, though relegated to the margins of modern biblical scholarship, stands at the very centre of the Byzantine exegetical and theological tradition. The Byzantine portrait of Paul places in bold relief the apostle’s dramatic conversion experience, his vision of the divine light, his self-identification with Christ, his ascent to the third heaven, and his gift of divine grace and wisdom—features that are generally grouped under the now politically incorrect category of Pauline “mysticism” and that remain by far the most neglected and misunderstood aspects of Paul’s life and work. These same features, however, figure prominently in the exegesis of the Greek fathers and especially the later Byzantine writers, in a unified tradition of Pauline interpretation extending from late antiquity to the end of the Palaiologan period and beyond. The Byzantine interpretation of Paul is an important area of study, both to better understand the later Byzantine theological tradition and for the retrieval of a uniquely meaningful option in the study of a figure whose importance for Christianity is second only to that of Christ himself.

Paul’s Rapture

The question of Paul’s visionary experiences and in particular his ascent or “rapture” (ἁρπαγή) into the third heaven is one which many modern scholars find disconcerting, if not a little alarming, inasmuch as the familiar Paul here changes into a believer in celestial wanderings. Accounts of “visions and revelations” (2 Cor. 12:1) and of journeys to “heaven” and “paradise” (2 Cor. 12:2, 4) make Paul seem more like a medieval Byzantine saint than a modern Protestant pastor, and argue for an image of the apostle as a man of “mystical” experiences in a way that scholars have found difficult to conceptualize. Yet none of this should be surprising, since Paul’s letters, as well as his depiction in the book of Acts, provide ample evidence of visionary experiences, revelations, and ecstasies; of miracles; of the indwelling of Christ and/or the Holy Spirit; of experiences of grace and spiritual transformation; and of personal union with Christ.

Paul’s account is the only firsthand description of an ascent to heaven to have survived from

the first century. It is tantalizingly brief—around fifty words—little more than an elliptical digression about “visions and revelations” embedded in a larger argument and therefore “difficult to understand” (2 Pet. 3:16). In the tradition of ironic boasting, Paul wrote of “a certain man” who was “caught up” into the “third heaven,” although he afterward stated that this man was “caught up” into “paradise,” where he heard “certain ineffable words that cannot be spoken.” To complicate matters still further, the apostle repeatedly noted that he did not know whether this experience took place “in the body or out of the body.” We are consequently left to wonder about the precise relation of the “third heaven” to “paradise,” which may perhaps be one and the same destination, unless Paul was speaking of a two-stage ascent, or perhaps of two separate ascents. Further ambiguity arises over whether or not this was a spiritual or a bodily experience; and we are told nothing about the content, meaning, or purpose of the revelation, or why the words that were heard cannot be communicated to others.

Despite these ambiguities—or perhaps because of them—this passage attracted considerable interest throughout the patristic and later Byzantine periods. On the whole, the church fathers accepted the account as entirely fitting and natural, recognizing in Paul's rapture a paradigm for their own spiritual experiences, a connection authorized by the influential Life of Antony. The connection itself, however, is much older, and appears in highly developed form already in Origen’s commentary on the Song of Songs, which conflated the connubial “inner chamber” with the apostle’s “third heaven.” The commentary survives only in a Latin translation (Commentarius in Canticum Canticorum), although the passage linking Paul’s ecstasy with Christian mystical experience is extant in Greek in the catena on the Song of Songs compiled by Prokopios of Gaza (ca. 460–526).

From at least the third century, spiritual writers interpreted Paul’s ascent as an expression

of the highest level of mystical experience. Undoubtedly, the most elaborate example of

such an interpretation is found in Maximos the Confessor, Ambigua 20. Maximos interpreted the event in the framework of his theology of divinization. He pointed out that divinization is not a natural potential of human nature, but the activity of divine grace, the reception of which requires a person to “go outside of himself,” that is, to enter a state of ecstasy, after the manner of Paul. Maximos subsequently embarked on a highly Dionysian interpretation of the apostle’s ascent to the third heaven, which, he argued, unfolded according to the three stages of purification, illumination, and mystical union.

The first stage encompasses (1) the “practical philosophy” of asceticism, (2) a renunciation of nature through virtue, or (3) a state of dispassion. The second stage is marked by (1) the transcendence of cognitions generated by the activity of sense perception, (2) the transcendence of time and space (i.e., the conditions in which objects of perception have their existence), or (3) “natural contemplation,” which is the comprehension of the intelligible foundations of phenomenal reality. The third and final stage is either (1) “dwelling” in God, (2) a restoration by grace to one’s divine source, or (3) initiation into “theological wisdom.” Because the latter triad is an ecstatic state marked by the cessation of both sensation and intellection, it is “not something that the apostle accomplished, but something that befell him,” and the only “activity” in actual operation belonged wholly to God. As for the meaning of the “third heaven,” Maximos offered two interpretations, either (1) the “boundary” or “limit” of each of the three stages that Paul attained or (2) the “three orders of angels immediately above us.” Through these orders Paul ascended by a process of negation and affirmation. By negating the knowledge of one order, the apostle was initiated into the rank immediately above it, “for the positive affirmation of the knowledge of what is ranked above is a negation of the knowledge of what is below, just as the negation of the knowledge of what is below implies the affirmation of what is above.” This process comes to a halt with the final negation of the “knowledge of God,” beyond which there can be no further affirmations, “since there is no longer any boundary or limit that could define or frame the negation.”

According to Maximos, it was the natural result of the apostle’s temporary loss of corporeal sensation and intellection that he did not know whether he was “in the body” or “outside the body.” Insofar as Paul had gone outside himself in ecstasy, his power of sense perception was inactive, and thus he was not “in the body.” But neither was he “outside the body,” insofar as “his intellective power was inactive during the time of his rapture.” Maximos averred that this is also why the words Paul heard cannot be repeated, for having, as it were, sounded in a realm beyond mind, they cannot be grasped by ordinary thought, or uttered through ordinary speech, or received by ordinary human hearing. Maximos concluded this complex interpretation by construing Paul’s threefold ascent as an expression of the spiritual progress that results from a life lived according to the Pauline virtues of “faith, hope, and love” (1 Cor. 13:13).

In Maximos’s reading of 2 Corinthians 12:1-4, Paul’s rapture is fully identified with ascetic contemplation and the experience of divinization. The “three heavens” signify—indeed simply are—the three stages of the spiritual life and their respective modes of cognition. The movement of “ascent” is thus a progression from lower to higher modes of cognition as the soul is increasingly abstracted from its bodily senses, passing into a realm beyond intellect. The condition of being “caught up,” of being “outside oneself,” is a signature Dionysian doctrine grounded on the ecstatic transport of Paul to the third heaven. Consistent with this tradition, Maximos allowed for an immediate experience of God in ecstasy, so that Paul’s rapture, far from being a unique or extraordinary event, coincided with the end for which Christian life is a preparation, namely, divinization. Among later Byzantine writers, this is the standard interpretation of 2 Corinthians 12:2-4, so that every saint becomes “another Paul (ἕτερος Παῦλος), caught up to the third heaven of theology” (Niketas Stethatos, Gnostic Chapters 44).

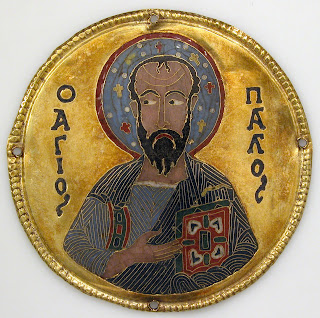

Byzantine Medallion with Saint Paul (ca. 1100)

Comments

Post a Comment