Historical Perspectives on Defining Byzantine Philosophy

On 6 March 2020, scholars will gather at Macquarie University for a promising Workshop: Historical Perspectives on Defining Byzantine Philosophy. The Workshop is convened by Dr Ken Parry and Dr Eva Anagnostou-Laoutides. Below are the abstracts of the presentations.

1. Vassilis Adrahtas, The relationship between theology and philosophy in the work of John Damascene and its bearing on the question of Byzantine philosophy

One of the problems that still persist with regards to the definition of Byzantine philosophy refers to the distinction between theology and philosophy and whether such a distinction is possible in the case of the history of ideas of Byzantium. This problem, however, is articulated in a rather simplistic way, insofar as it poses – anachronistically, I would dare say – theology and philosophy as two totally different fields of reference. But Byzantine thinkers seem to have opted for quite an alternative perspective: a perspective of co-inherence.

If Byzantine philosophy is to be traced from the 8th century onwards, the bearing of John Damascene’s philosophically informed and highly influential work seems to have played a major role in setting the stage for the emergence of the distinctive phenomenon we may call Byzantine philosophy: neither too Greek as to cease being Christian, nor too Christian as to be identified with theology. By necessity this involved a long process of critical demarcations and selections, focusing emphatically on gnoseology and/or logic, as well as establishing a new thematics.

In the transition from Late Antiquity to the Middle Ages, John Damascene not only recapitulated patristic tradition, but also opened up theology to the ‘other’ in ways unprecedented since Origen. The great Alexandrian had put forward a bold religio-philosophical synthesis which, although greatly influential, did not become normative, mainly because philosophy remained in his work all too Greek. This will become for theology an acute issue of critical self-consciousness over the ensuing centuries facilitating finally the emergence of what we witness in the case of John Damascene: an integral relationship between theology and philosophy.

In the work of John Damascene we see for the first time a programmatic and systematic presentation of a distinctively Christian philosophy, which undoubtedly has theology as a conceptual frame of reference but at the same time is enabled to explore reflectively and critically the traditional spectrum of philosophical ideas. In other words, John Damascene resolved an age-old tension by elaborating on the Greek tropos of philosophy, on the one hand, and by transcending its Greek eidos, on the other. The Damascenean solution created the outline of what the Byzantines could confidently – at last – turn into their own philosophy.

2. Eva Anagnostou-Laoutides, Wine and Philosophical Mania from the Symposium to the Christian Eucharist

The paper investigates the reception of Platonic and neoplatonic ideas about wine and its influence on the intellect in early Christian thinkers who strove to articulate the meaning and importance of the eucharist (Norris 2004: 40-41; Lampe 2003: 260-284). Proclus’ influence on Christian theology, mainly through ps-Dionysius’ ability to dress Proclean metaphysics “in Christian draperies,” is well-established in scholarship (Struck 2004: 257). Here, however, I argue that ps.-Dionysius’ understanding of the eucharist in Proclean terms, infused with Plotinus’ image of the intellect as being “drunk with nectar” (Enn.VI7.35), presupposes a deeper engagement with pagan philosophical traditions.

I start with a review of Socrates’ profile as a drinker in the Symposium; the return to Plato is necessary because both the Jewish traditions that were absorbed in the New Testament (Bacchiocchi 2001: 63-87) and the then popular Stoic attitudes to wine consumption (SVF I.229 and III.237) rejected the use of wine as a means of achieving spiritual growth. On the contrary, the Socratic way of drinking with its anagogic character echoes the Christian eucharistic tradition that aims to commemorate the divine passion and achieve a communion with God (De Andia 2005: 38-53). In my view, ps.-Dionysus’ appreciation of Platonic inebriation was mediated by Clement of Alexandria, who belongs to the same intellectual milieu as Plotinus and Iamblichus. Accordingly, the Christian doctrine of the eucharist reflects the intellectual exchanges of pagans and Christians from the second to the fourth century CE.

Indicative Bibliography:

1. S. Bacchiocchi, Wine in the Bible. A Biblical Study on the Use of Alcoholic Beverages (Berrien Springs, MI 2001).

2. Y. De Andia, ‘La trés divine Céne…archisymbole de tout sacrament (EH 428B). Symbole et eucharistie chez Denys l’Aréopagite et dans la tradition antiochienne,’ in I. Perczel, R. Forrai, G. Geréby (eds), The Eucharist in Theology and Philosophy: Issues of Doctrinal History in East and West from the Patristic Age to the Reformation (Leuven 2005) 37-66.

3. R.A. Norris, ‘The Apologists,’ in F. Young, L. Ayres and A. Louth (eds), The Cambridge History of Early Christian Literature (Cambridge 2004) 33-66.

4. P. Lampe, From Paul to Valentinus: Christians at Rome in the First Two Centuries (Minneapolis 2003).

5. P. Struck, Birth of the Symbol: Ancient Readers at the Limits of their Texts (Princeton 2004).

3. Amber Bremner, Platonic Influences in the Testament of Job

The Testament of Job is a Jewish document believed by scholars to have been written at some point between the first century BCE and the first century CE. Though the earliest extant copy is written in Coptic, the original is believed to have been written in Greek and is composed in the style of a Testament, a genre defined by Spittler as a text where ‘a wise, aged (and usually dying) father imparts final words of ethical counsel to his attentive offspring.’ The Testament of Job is a complete retelling of the Hebrew version contained within the Old Testament with many significant differences. One of these differences is a highly philosophical and ascetic perspective of the suffering of Job which is often expressed in the language and metaphor of Greek philosophy and shows strong elements of Platonic thought. Rather than the confused, bewildered and angry Job of the Hebrew narrative, the testament portrays Job as a wise and almost Socratic figure who speaks to the friends who pity his suffering of another realm where his true throne resides. He declares that ‘my throne is in a holy land, and its glory lies in an unchangeable realm…the rivers in the land of my throne will never dry up and disappear. They will flow forever.’ (T.Job 33) These words represent ideas within the text which reflect Plato’s theory of forms, his ideas regarding a duality between body and soul and an understanding of the soul’s immortality. This paper will examine the Testament of Job and its relation to Platonic thought in order to gain further knowledge of the influence of Plato upon the Judaism of the Second Temple period.

4. Michael Champion, Mental health and defining philosophy as practice of death

Late-antique prolegomena to philosophy helped to define the parameters of Neoplatonic thinking and were influential into the Byzantine period. They set out and comment on six standard definitions of philosophy and thereby provide beginner students of philosophy with an idea of the contours and scope of their subject. In this paper, I will focus on the claim that philosophy is the practice of death. This claim had long worried Platonists and philosophers in other schools, famously led to the suicide of Kleombrotos, and resulted in a long commentary tradition on the question of the rightness of suicide and its relation to the practice of philosophy. Philosophers, doctors, ascetics and clerics entered this debate and each claimed special expertise to identify and promote healthy forms of the practice of death. The definition of philosophy as the practice of death therefore places philosophical self-definition within a larger intellectual, religious, and social context. I trace some key elements in the debate as presented in the late-antique prolegomena in order to cast light on the self-understanding of Neoplatonists about how to define philosophy and to set it in the larger context of contests of expertise in the period.

5. Matthew R. Crawford, Demiurgical Dishonoring and Divine Envy: Echoes of Cyril of Alexandria’s Critique of the Timaeus in Later Neoplatonic Texts

The bulk of book two of Cyril of Alexandria’s treatise Contra Julianum is taken up with a sustained engagement with the Emperor Julian’s claim that Plato’s Timaeus is a superior cosmogony than the Mosaic account of creation in Genesis. Cyril’s central critique of the Timaeus is that Plato’s Demiurge is guilty of dishonouring his creation by not creating them directly but instead using the younger gods as his intermediaries. The reason for his having done so, Cyril speculates, is that he was envious of his creatures and did not wish to share his own goods with them. Few scholars have considered Contra Julianum in relation to late antique philosophical texts, and in this paper I intend to draw attention to several echoes of Cyril’s critique of the Timaeus in later Neoplatonic writings, including Proclus’ Commentary on the Timaeus, Philoponus’ De opificio mundi and De aeternitate mundi, and Zacharias’ Ammonius sive De mundi opificio disputatio. These later texts show that Cyril’s criticism of Plato’s Demiurge shaped subsequent philosophical debate by highlighting some of the more fundamental distinctions between Neoplatonism and Christian orthodoxy.

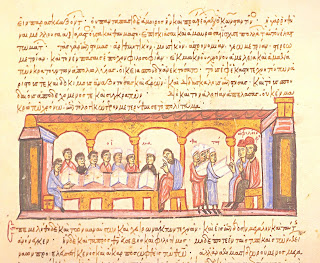

6. Ken Parry, Theory and Practice of Cult Images in Neoplatonism and Byzantine Christianity

The role of cult images in Neoplatonism and Byzantine Christianity has received attention from scholars working in these respective fields, but not much has been done by way of a comparative study. My aim in this paper is to look at what these traditions had in common as well as how they differed on this question. Given the common Hellenistic heritage shared by Greek-speaking Platonists and Christians, images of the gods and holy persons were central to their religious practice. It was particularly the cultic practices they shared that highlights their attitude to divine embodiment and the material world. The modern tendency to view Platonism and Christianity as dualistic, and to focus primarily on their philosophical and theological theories, has led to the neglect of their ritual habits. The justification for making images and venerating them is one thing but understanding what these communities expected from their images is another. The theurgic and liturgic aspects of the image cult point to the central role piety and observance had in expressing their respective worldviews. In the case of Neoplatonism, the practice of animating statues was a generally accepted feature of the philosophical way of life, but it was not until the period of iconoclasm in Byzantium that Christians were required to defend their devotion to icons. The fact that it was fellow Christians who instigated the movement against icons and their veneration shows the importance they had acquired over several centuries of criticizing pagan practices.

7. David Runia, The Placita of Aëtius: a new edition after 140 years and its relevance for later Greek philosophy

In June of this year the publication will take place of a new edition of the Placita of Aetius, to be published by Brill in the Philosophia Antiqua series. It will replace the edition of Hermann Diels in his celebrated Doxographi Graeci (Berlin 1879), one of the most celebrated and influential works of nineteenth century scholarship. I will first give the necessary background on this little-known but important work for the study of ancient philosophy. Although it is mainly associated with early Greek philosophy and indeed only deals with the views of philosophers up to the first century BCE, the work in fact has a strong connection to later Greek and even Islamic philosophy. The primary reason for this is that much of the evidence for the not fully preserved work is dependent on later witnesses and their philosophical and theological interests. I will also reflect on whether its interest goes further than that.

8. George Steiris, Redefining Pletho’s Philosophical Sources: Pletho as a reader of the Corpus Dionysiacum

Georgios Gemistos “Pletho” (1355-1454) was the most prominent scholar of 15th century-Byzantium. Whilst most Pletho scholars tend to emphasize his debts to Neoplatonism, especially Proclus, they have not devoted enough attention to the relation between Pletho’s texts and the Corpus Dionysiacum. Chatzimichael contends that a careful reading of Pletho’s texts would reveal hitherto unnoticed affinities with Pseudo Dionysius’ views, because they were both indebted to Proclus. Hladky presents Plethonic ontology as compatible with the Pseudo Dionysian one. According to Woodhouse, Pletho’s alleged debts to Pseudo Dionysius could also be attributed to Neoplatonism. On the contrary, Gersh holds that Pletho aspired to a Platonism bereft of Christian influences and, that, as a result, he wished to separate the Zoroastrian from the Dionysian elements in his philosophy. Siniossoglou points out the divergences between Pletho and Pseudo Dionysius to vindicate his thesis about Pletho’s paganism. In this essay, I attempt to scrutinize the way Pletho addresses the Corpus Dionysiacum. I argue that Pletho was originally a political thinker and he gradually evolved into a political philosopher in order to support his political vision. In this endeavour the Corpus Dionysiacum was extremely useful for him so as he elaborates his political ontotheology.

1. Vassilis Adrahtas, The relationship between theology and philosophy in the work of John Damascene and its bearing on the question of Byzantine philosophy

One of the problems that still persist with regards to the definition of Byzantine philosophy refers to the distinction between theology and philosophy and whether such a distinction is possible in the case of the history of ideas of Byzantium. This problem, however, is articulated in a rather simplistic way, insofar as it poses – anachronistically, I would dare say – theology and philosophy as two totally different fields of reference. But Byzantine thinkers seem to have opted for quite an alternative perspective: a perspective of co-inherence.

If Byzantine philosophy is to be traced from the 8th century onwards, the bearing of John Damascene’s philosophically informed and highly influential work seems to have played a major role in setting the stage for the emergence of the distinctive phenomenon we may call Byzantine philosophy: neither too Greek as to cease being Christian, nor too Christian as to be identified with theology. By necessity this involved a long process of critical demarcations and selections, focusing emphatically on gnoseology and/or logic, as well as establishing a new thematics.

In the transition from Late Antiquity to the Middle Ages, John Damascene not only recapitulated patristic tradition, but also opened up theology to the ‘other’ in ways unprecedented since Origen. The great Alexandrian had put forward a bold religio-philosophical synthesis which, although greatly influential, did not become normative, mainly because philosophy remained in his work all too Greek. This will become for theology an acute issue of critical self-consciousness over the ensuing centuries facilitating finally the emergence of what we witness in the case of John Damascene: an integral relationship between theology and philosophy.

In the work of John Damascene we see for the first time a programmatic and systematic presentation of a distinctively Christian philosophy, which undoubtedly has theology as a conceptual frame of reference but at the same time is enabled to explore reflectively and critically the traditional spectrum of philosophical ideas. In other words, John Damascene resolved an age-old tension by elaborating on the Greek tropos of philosophy, on the one hand, and by transcending its Greek eidos, on the other. The Damascenean solution created the outline of what the Byzantines could confidently – at last – turn into their own philosophy.

2. Eva Anagnostou-Laoutides, Wine and Philosophical Mania from the Symposium to the Christian Eucharist

The paper investigates the reception of Platonic and neoplatonic ideas about wine and its influence on the intellect in early Christian thinkers who strove to articulate the meaning and importance of the eucharist (Norris 2004: 40-41; Lampe 2003: 260-284). Proclus’ influence on Christian theology, mainly through ps-Dionysius’ ability to dress Proclean metaphysics “in Christian draperies,” is well-established in scholarship (Struck 2004: 257). Here, however, I argue that ps.-Dionysius’ understanding of the eucharist in Proclean terms, infused with Plotinus’ image of the intellect as being “drunk with nectar” (Enn.VI7.35), presupposes a deeper engagement with pagan philosophical traditions.

I start with a review of Socrates’ profile as a drinker in the Symposium; the return to Plato is necessary because both the Jewish traditions that were absorbed in the New Testament (Bacchiocchi 2001: 63-87) and the then popular Stoic attitudes to wine consumption (SVF I.229 and III.237) rejected the use of wine as a means of achieving spiritual growth. On the contrary, the Socratic way of drinking with its anagogic character echoes the Christian eucharistic tradition that aims to commemorate the divine passion and achieve a communion with God (De Andia 2005: 38-53). In my view, ps.-Dionysus’ appreciation of Platonic inebriation was mediated by Clement of Alexandria, who belongs to the same intellectual milieu as Plotinus and Iamblichus. Accordingly, the Christian doctrine of the eucharist reflects the intellectual exchanges of pagans and Christians from the second to the fourth century CE.

Indicative Bibliography:

1. S. Bacchiocchi, Wine in the Bible. A Biblical Study on the Use of Alcoholic Beverages (Berrien Springs, MI 2001).

2. Y. De Andia, ‘La trés divine Céne…archisymbole de tout sacrament (EH 428B). Symbole et eucharistie chez Denys l’Aréopagite et dans la tradition antiochienne,’ in I. Perczel, R. Forrai, G. Geréby (eds), The Eucharist in Theology and Philosophy: Issues of Doctrinal History in East and West from the Patristic Age to the Reformation (Leuven 2005) 37-66.

3. R.A. Norris, ‘The Apologists,’ in F. Young, L. Ayres and A. Louth (eds), The Cambridge History of Early Christian Literature (Cambridge 2004) 33-66.

4. P. Lampe, From Paul to Valentinus: Christians at Rome in the First Two Centuries (Minneapolis 2003).

5. P. Struck, Birth of the Symbol: Ancient Readers at the Limits of their Texts (Princeton 2004).

3. Amber Bremner, Platonic Influences in the Testament of Job

The Testament of Job is a Jewish document believed by scholars to have been written at some point between the first century BCE and the first century CE. Though the earliest extant copy is written in Coptic, the original is believed to have been written in Greek and is composed in the style of a Testament, a genre defined by Spittler as a text where ‘a wise, aged (and usually dying) father imparts final words of ethical counsel to his attentive offspring.’ The Testament of Job is a complete retelling of the Hebrew version contained within the Old Testament with many significant differences. One of these differences is a highly philosophical and ascetic perspective of the suffering of Job which is often expressed in the language and metaphor of Greek philosophy and shows strong elements of Platonic thought. Rather than the confused, bewildered and angry Job of the Hebrew narrative, the testament portrays Job as a wise and almost Socratic figure who speaks to the friends who pity his suffering of another realm where his true throne resides. He declares that ‘my throne is in a holy land, and its glory lies in an unchangeable realm…the rivers in the land of my throne will never dry up and disappear. They will flow forever.’ (T.Job 33) These words represent ideas within the text which reflect Plato’s theory of forms, his ideas regarding a duality between body and soul and an understanding of the soul’s immortality. This paper will examine the Testament of Job and its relation to Platonic thought in order to gain further knowledge of the influence of Plato upon the Judaism of the Second Temple period.

4. Michael Champion, Mental health and defining philosophy as practice of death

Late-antique prolegomena to philosophy helped to define the parameters of Neoplatonic thinking and were influential into the Byzantine period. They set out and comment on six standard definitions of philosophy and thereby provide beginner students of philosophy with an idea of the contours and scope of their subject. In this paper, I will focus on the claim that philosophy is the practice of death. This claim had long worried Platonists and philosophers in other schools, famously led to the suicide of Kleombrotos, and resulted in a long commentary tradition on the question of the rightness of suicide and its relation to the practice of philosophy. Philosophers, doctors, ascetics and clerics entered this debate and each claimed special expertise to identify and promote healthy forms of the practice of death. The definition of philosophy as the practice of death therefore places philosophical self-definition within a larger intellectual, religious, and social context. I trace some key elements in the debate as presented in the late-antique prolegomena in order to cast light on the self-understanding of Neoplatonists about how to define philosophy and to set it in the larger context of contests of expertise in the period.

5. Matthew R. Crawford, Demiurgical Dishonoring and Divine Envy: Echoes of Cyril of Alexandria’s Critique of the Timaeus in Later Neoplatonic Texts

The bulk of book two of Cyril of Alexandria’s treatise Contra Julianum is taken up with a sustained engagement with the Emperor Julian’s claim that Plato’s Timaeus is a superior cosmogony than the Mosaic account of creation in Genesis. Cyril’s central critique of the Timaeus is that Plato’s Demiurge is guilty of dishonouring his creation by not creating them directly but instead using the younger gods as his intermediaries. The reason for his having done so, Cyril speculates, is that he was envious of his creatures and did not wish to share his own goods with them. Few scholars have considered Contra Julianum in relation to late antique philosophical texts, and in this paper I intend to draw attention to several echoes of Cyril’s critique of the Timaeus in later Neoplatonic writings, including Proclus’ Commentary on the Timaeus, Philoponus’ De opificio mundi and De aeternitate mundi, and Zacharias’ Ammonius sive De mundi opificio disputatio. These later texts show that Cyril’s criticism of Plato’s Demiurge shaped subsequent philosophical debate by highlighting some of the more fundamental distinctions between Neoplatonism and Christian orthodoxy.

6. Ken Parry, Theory and Practice of Cult Images in Neoplatonism and Byzantine Christianity

The role of cult images in Neoplatonism and Byzantine Christianity has received attention from scholars working in these respective fields, but not much has been done by way of a comparative study. My aim in this paper is to look at what these traditions had in common as well as how they differed on this question. Given the common Hellenistic heritage shared by Greek-speaking Platonists and Christians, images of the gods and holy persons were central to their religious practice. It was particularly the cultic practices they shared that highlights their attitude to divine embodiment and the material world. The modern tendency to view Platonism and Christianity as dualistic, and to focus primarily on their philosophical and theological theories, has led to the neglect of their ritual habits. The justification for making images and venerating them is one thing but understanding what these communities expected from their images is another. The theurgic and liturgic aspects of the image cult point to the central role piety and observance had in expressing their respective worldviews. In the case of Neoplatonism, the practice of animating statues was a generally accepted feature of the philosophical way of life, but it was not until the period of iconoclasm in Byzantium that Christians were required to defend their devotion to icons. The fact that it was fellow Christians who instigated the movement against icons and their veneration shows the importance they had acquired over several centuries of criticizing pagan practices.

7. David Runia, The Placita of Aëtius: a new edition after 140 years and its relevance for later Greek philosophy

In June of this year the publication will take place of a new edition of the Placita of Aetius, to be published by Brill in the Philosophia Antiqua series. It will replace the edition of Hermann Diels in his celebrated Doxographi Graeci (Berlin 1879), one of the most celebrated and influential works of nineteenth century scholarship. I will first give the necessary background on this little-known but important work for the study of ancient philosophy. Although it is mainly associated with early Greek philosophy and indeed only deals with the views of philosophers up to the first century BCE, the work in fact has a strong connection to later Greek and even Islamic philosophy. The primary reason for this is that much of the evidence for the not fully preserved work is dependent on later witnesses and their philosophical and theological interests. I will also reflect on whether its interest goes further than that.

8. George Steiris, Redefining Pletho’s Philosophical Sources: Pletho as a reader of the Corpus Dionysiacum

Georgios Gemistos “Pletho” (1355-1454) was the most prominent scholar of 15th century-Byzantium. Whilst most Pletho scholars tend to emphasize his debts to Neoplatonism, especially Proclus, they have not devoted enough attention to the relation between Pletho’s texts and the Corpus Dionysiacum. Chatzimichael contends that a careful reading of Pletho’s texts would reveal hitherto unnoticed affinities with Pseudo Dionysius’ views, because they were both indebted to Proclus. Hladky presents Plethonic ontology as compatible with the Pseudo Dionysian one. According to Woodhouse, Pletho’s alleged debts to Pseudo Dionysius could also be attributed to Neoplatonism. On the contrary, Gersh holds that Pletho aspired to a Platonism bereft of Christian influences and, that, as a result, he wished to separate the Zoroastrian from the Dionysian elements in his philosophy. Siniossoglou points out the divergences between Pletho and Pseudo Dionysius to vindicate his thesis about Pletho’s paganism. In this essay, I attempt to scrutinize the way Pletho addresses the Corpus Dionysiacum. I argue that Pletho was originally a political thinker and he gradually evolved into a political philosopher in order to support his political vision. In this endeavour the Corpus Dionysiacum was extremely useful for him so as he elaborates his political ontotheology.

Hello, Thank you so much for writing such an informational blog. If you are facing trouble in your Mozilla Firefox then you can get quick and best support here, for more info click on given links-

ReplyDeletereset mozilla thunderbird email password

Fix Slowness Crashing Error Messages Firefox

Mozilla Thunderbird Not Working

Firefox Consistently Crashes Search Gmail

Reset Mozilla Thunderbird Email Password

Mozilla Thunderbird not Responding or Working

fix Mozilla Firefox error code 2324

print web pages in mozilla firefox