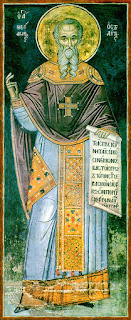

Icon and Idol in the Iconology of Theodore the Stoudite

With the kind permission of Dr Ken Parry, here is an excerpt from his article, ‘Theodore the Stoudite: The Most “Original” Iconophile?’ published in Jahrbuch der Österreichischen Byzantinistik (2018), 261-75.

In countering the accusation of idolatry, as well as

justifying their re-reading of the Exodus prohibition against images, the

iconophiles drew a distinction between an icon and an idol. They utilized a

distinction inherent in philosophical discussions of nominal definitions. In

his Posterior Analytics Aristotle proposed the compound “goat-stag”

(τραγέλαφος) as the name of a non-existent thing. However, Plato had earlier

used the example of a goat-stag as painted by an artist who combines two animals

in one. These mythological creatures, such as gorgons, sirens and griffins,

were to be seen in Greek art. This idea of an imaginary animal was discussed by

Origen who gave the example of a centaur because it exists only in the

imagination. In doing so, he drew a distinction between an image that is

imaginary and an image that is a likeness.

A similar distinction is found in Nikephoros, but the

patriarch is unlikely to have read Origen’s Homily on Exodus in which

this distinction is found. This is what Nikephoros has to say: “An idol is a

work of fiction and the representation of a non-existent (ἀνυποστάτων) being,

such things as the Hellenes out of their lack of good sense and atheism made

into representations, namely tritons, centaurs and other phantasms which do not

exist. And in this respect icons and idols are to be distinguished from one

another; those not accepting the distinction should rightly be called

idolaters.”

Here the contrast is between a composite image of the

imagination and icon of an existing archetype. In making his distinction Origen

explicated Paul’s statement that “an idol is nothing in the world” (1 Cor.

8:4), a remark that Celsus in his work Against the Christians seems to

have known and which Origen criticised him for misappropriating. Origen

interprets it to mean that because an idol is without a prototype it must lack

historicity and therefore credibility. Paul’s statement is discussed by

Macarius Magnes in the late fourth century in his Apocriticus, in which

he draws attention to the difference between an idol and a likeness painted on

boards.

For Theodore the Stoudite, Christian images deserve to be

called icons because the definition of an icon implies a prototype which has a

relative and homonymous relationship with its copy. But how does this

definition apply to so-called icons not-made-by-hand (ἀχειροποίητος), in which

there is no human intermediary between the prototype and the image? According

to Theodore, whatever is artificial imitates something natural, for nothing

would be called artificial if it were not preceded by something natural.

Although it is not strictly true that whatever is artificial imitates something

natural, it may be conceded that a work of the imagination could be said to be

natural, in so far as it has been conceived by an artist who is himself part of

the natural world. But for Theodore a work of the imagination is not properly

speaking an archetypal form; there is no place for abstract or

non-representational imagery in his image theory. The mimetic theory that lies

behind his iconology seems to preclude the representation of non-natural forms.

It is the reality of the archetype that he is keen to emphasise because it

legitimises Christian image-making over the images of the non-Christian world.

Although he suggests that mental as well as physical perceptions

may be depicted, he would want to qualify this by adding that not everything

that is depicted is an icon. It is the content and not the form that

distinguishes the icon from other types of images. Nowhere does he state that

the form of the icon must be two-dimensional or painted on a wooden panel. And

because he does not specify what form the icon should take, it must be assumed

that he takes the iconographic tradition for granted. This is to be expected,

given that it is “who” is depicted rather than “how” they are depicted that defines

the icon. From this we might infer that any image of Christ, regardless of

whether it is two or three dimensions, constitutes an icon. In fact, it is not

until the later period that Byzantine authors censure images in the round and

do so largely in response to medieval western art. Yet despite the decline in

freestanding sculpture from the sixth century, there was no official church

prohibition against three-dimensional images. And there is no evidence that

iconoclasts, or iconophiles for that matter, wanted to destroy the ancient

statues that adorned the boulevards of Constantinople.

We know there is something of a mismatch between what we see

in the Byzantine icon and what the Byzantines tell us they saw. Where we see

semi-abstract and attenuated figures, which are far from naturalistic in the

modern sense of the term, the Byzantines saw hyper-realistic renditions on the

verge of speaking or weeping. The literary genre of the ekphrasis

invariably speaks of the true likeness of the portrait, often blurring the

distinction between archetype and image. The granting of a degree of autonomy

to the icon is carried over into hagiographical works that discuss

miracle-working icons. Theodore does not describe exactly what Christ should

look like in his icon (Epistle 359); he is not interested in his

physical features as such, even though he argues for his hypostatic

individuality at the philosophical level. He might have described the types of

portraits of Christ familiar to him, but for Theodore it was sufficient to

claim that his icon (unlike the Gospels) was contemporaneous with his earthly

sojourn. Given the absence of a physical description of Christ in the New Testament

this descriptive gap was filled by icons not-made-by-hands. These images

eliminated the human element regarding differences in style.

Returning for a moment to the depiction of individual

physical features in the icon, there is a passage of interest in a work

entitled On the Constitution of Man by the ninth-century iatrosophist and

physician, Meletios the Monk, from the Holy Trinity Monastery at Tiberiopolis

in Asia Minor. The title of Meletios’ work shows his reliance on the

Hippocratic tradition via Galen and Nemesis of Emesa, but his ninth-century

date is far from certain. In talking about himself he refers to “my friend

Meletios”, and points out that nobody else may be mistaken for him because of

his individual characteristics.

“For the idiosyncrasies of Meletios, since he is an

individual (ἄτομον), cannot be perceived in anyone else; such as being a

Byzantine, a physician, short, blue-eyed, snub-nosed, suffering from gout,

having a certain scar on the forehead, being the son of Gregory. For all these

things together have constituted Meletios and they cannot be perceived in

anybody else … Meletios when, standing, he reads or bleeds or cauterises

somebody, proves himself separate from the rest of the brethren.”

This emphasis on personal characteristics or accidental properties may be directly related to the question of the nature of the hypostasis represented in icons. We may note John of Damascus on separable and inseparable accidents in his Institutio elementaris, where he speaks of the man with a snub nose and the man with the hooked nose, and the impossibility of them being the same person. For Theodore, there is danger of idolatry from the icon as well as the idol. Distinguishing them theoretically is one thing but knowing the intention of the worshipper is another. The intentionality of the worshipper is central to the veneration of the icon because orthopraxis is concomitant with orthodoxy.

The problem is that the outward act of veneration appears

the same, whether we are offering veneration to the emperor or to Christ, but

the intention is different. By understanding this intentional difference we are

able to offer the proper worship due to God alone, from the veneration due to

the Theotokos as Theotokos and to the saints as saints. Theodore is here

operating with the distinction between adoration (λατρεία) and veneration

(προσκύνησις), which had been systematised by John of

Damascus and taken for granted by the bishops at Nicaea II

in 787, and which was to some extent recognised by Theodulf of Orleans in the Opus

Caroli regis contra synodum of the 790s. Theodore goes on to condemn those

who do not acknowledge this difference and who refuse to offer the appropriate veneration

due to those shown in their icons (Epistle 551).

It may be important to know the correct veneration due to

images of Christ, the Theotokos and the saints, but there is one type of image

that appears to lie outside the iconophile taxonomy of images, and that is

images of intellectual or spiritual beings, notably angels. Christ, his mother,

and the saints are circumscribed by time and place and are therefore able to be

depicted, but angels, it would appear, being outside of time and place, are

uncircumscribed and therefore beyond depiction. Time and place are a priori

determinants of circumscription and circumscription is a prerequisite of representation.

If something cannot be circumscribed it cannot be depicted, at least that is

what the iconoclasts argued.

Theodore meets this objection in his Third Antirrheticus

in the following way. He writes: “In comparison with a dense body, the nature

of angels is incorporeal, but in comparison with the divine nature, angels are

neither incorporeal nor uncircumscribable (ἀπερίγραπτος), for what is properly

incorporeal is unlimited and uncircumscribed, but this applies only to the

divine nature. An angel, however, is limited by place (τόπος) and is thus

circumscribable.”

Comments

Post a Comment